- 30 October, 2023

- Media about us

“The people of the Republic of Armenia have entrusted the government with the mandate to establish the rule of law and order. As a result of the Patrol Police Service, the citizens of Armenia should see a new level of law and order on the streets of the capital, Yerevan. This is the most important mission that you must fulfill.”

In July 2021, Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan delivered a speech that marked the initiation of the Patrol Police Service in Yerevan, promising the long-awaited establishment of a new and prestigious police force in the country.

“But we must acknowledge that the rule of law, the enforcement of law and order, is established and not only through punishments and sanctions, but also through guiding, supporting, and helping citizens to conform and behave appropriately within the framework of law and order. On the other hand, citizens should see that rights and laws are a phenomenon that comes to their aid and supports them, rather than create obstacles for them.”

The reforms implemented and planned in post-revolutionary Armenia, which aimed to establish the rule of law, fight corruption, and establish an independent judiciary, were hindered by the devastating war of 2020, resulting in slowdowns or failure.

The promising start of the Police reforms was seen as a way to address several problems in the country, from transforming road safety by shifting the role of a police officer from being solely focused on issuing fines, punishing individuals, and accepting bribes to becoming an actual protector of civilians.

The “Old” Police

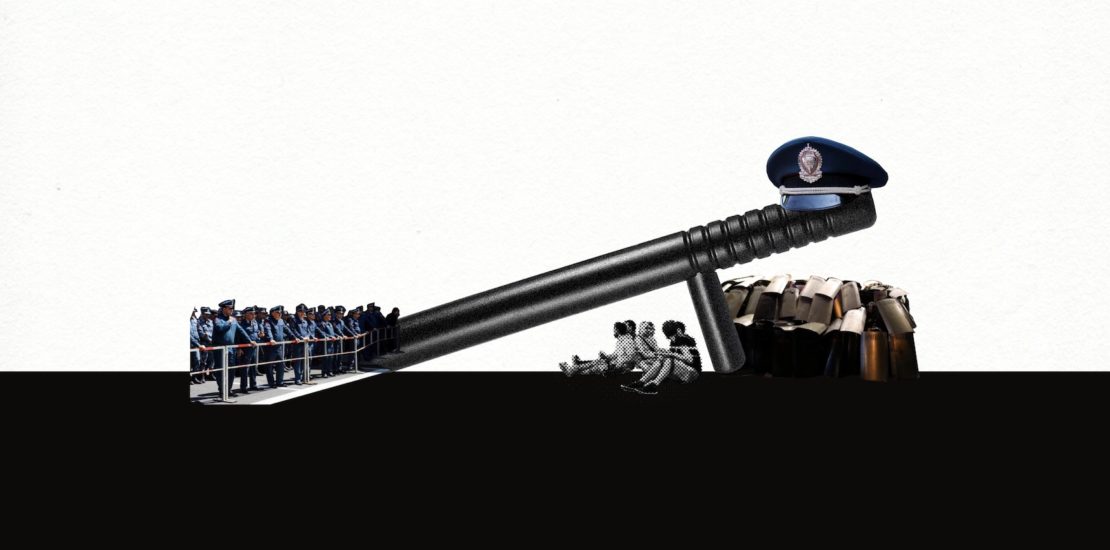

The conventional perception of the Armenian police is rooted in the Soviet militia, where the police are seen as a corrupt and violent entity that takes orders from the government to suppress citizens. In reality, the Armenian government has not taken any action to address this perception and has even supported and concealed incidents of police violence, which has further eroded public trust in law enforcement.

Police brutality and illegal actions have gained the attention of many international human rights organizations. A Human Rights Watch report from 2017 found that the Armenian government “failed to ensure full accountability for police violence against largely peaceful protesters and journalists” in 2016, following the Sasna Tsrer attack on a police station.

“Police arbitrarily detained hundreds of protesters between July 17-31, 2016 and beat many of them, in some cases severely. They did not allow some detainees to get prompt medical care for their injuries,” the report stated.

In 2018, the European Court of Human Rights found that the Armenian authorities failed to investigate allegations of police violence during the February-March 2008 protests following the heavily contested presidential elections. Instead, they prosecuted only protesters.

The 2017 Human Rights report from the U.S. Embassy in Yerevan highlighted that “police abuse of suspects during their arrest, detention, and interrogation” continued to be a “significant problem” in Armenia. The report emphasized that this mistreatment often took place in police stations, which lacked public monitoring unlike prisons and police detention facilities.

The investigation of alleged crimes committed by the police, the cases of violence, and the widespread rumors about corruption at all levels of the police did not become a hot topic of public discourse until the 2018 revolution.

The widespread support for the Pashinyan government and the ambitious reform plans of the ruling party raised hopes for a change in the system. However, it did not take long for those who had initially supported the changes to become skeptical about the results.

How It Began: The Revolution

“The Police is ours!” (Ոստիկանը մերն ա) slogan used by the revolutionary leaders quickly won the heart of the protesters. The aim was to convince police officers to join the revolution and put an end to the detention and violence against those who took the streets in Spring 2018.

The protests initially began as a complaint against the government’s policies, corruption, and the economic situation in Armenia. Led by journalist and opposition politician Nikol Pashinyan — who is now Armenia’s Prime Minister — the slogans of the protests adopted populist approaches that had a significant impact on the process and the mood in the streets and on the police.

The revolution in the streets of Armenia’s capital Yerevan ended without any major conflict between the police and the hundreds of thousands of protesters, despite widespread detentions, occasional incidents of violence and clashes.

Following the change of power, Valeriy Osipyan, who had overseen the police actions during the street protests as the deputy head of the Armenian capital’s police, was appointed as the chief of police. This marked the first internal change in the police force after the revolution. However, despite his initial support for the revolution, Osipyan and Pashinyan did not work together for long. Osipyan was fired from his position as the Prime Minister’s adviser in October 2019, which he had been appointed to after leaving his post as chief of police. Neither Osipyan nor the ruling party provided any clarification regarding the reasons for the alleged fallout between them.

In 2020, Nikol Pashinyan appointed Vahe Ghazaryan, the former head of the Ijevan Police Department, as chief of the Armenian Police.

Civil society accused the Armenian government of straying from the path of reforms.

The Reform Agenda

The reforms in the Armenian Police had been under discussion long before the revolution. However, many doubted the sincerity of the Serzh Sargsyan government in implementing these reforms and did not anticipate significant changes in what appeared to be the core issue of the police: the values and principles followed by police officers.

Daniel Ioannisyan, a democracy watchdog and project coordinator for the Union of Informed Citizens NGO, believes that the reforms discussed prior to the revolution were merely “structural reforms”, and did not aim to “change the underlying values of the law enforcement system.”

“The concept of the Patrol Police had been discussed since 2012, but it lacked an ideological foundation,” he said. “These reforms focused on administrative and structural changes, planning to merge different police departments and provide them with new and beautiful cars.”

Things “fundamentally” changed when the Pashinyan government granted the Ministry of Justice the power to coordinate and oversee reforms, according to Ioannisyan. Working with NGOs, including the Union of Informed Citizens, the initial phases of the changes appeared to be satisfactory for everyone.

“It was evident that we needed to establish a police force focused on serving society, rather than punishing it,” Ioannisyan explains. “This concept was completely new.”

In 2020, the NGOs joined the reform council, coinciding with the creation of the Patrol Police.

A strategy for the reforms was prepared and published, outlining the main changes that were to take place in the system.

The aim of the reforms was to establish a Patrol Police that would replace both the road police and the regular police forces. They would oversee road and civil safety throughout the country. As part of these reforms, the police would be placed under the Ministry of Internal Affairs, resulting in changes to the long-standing practices followed by the police.

The official reform strategy states that the goal of the police reform is to transform the Police into a professional and technologically advanced organization. It emphasizes the importance of integrity, respect, and the ability to address modern challenges. The strategy also highlights the creation of a new image for police officers that aligns with the principles of a democratic legal system.

The reform strategy includes specific sections dedicated to the protection of human rights. This includes measures to prevent torture, provide detainees with understandable information about their rights, offering medical services in detention facilities, and addressing issues related to the protection of personal data by various police services (such as database maintenance, data transfer, and storage).

As part of the reforms, one of the changes was the recreation of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. Armenia previously had an interior ministry, but it was abolished by former President Robert Kocharyan. He transformed the police into a separate structure that answered directly to him, around two decades ago. Since the country’s transition to a parliamentary system of government in 2018 under Serzh Sargsyan, the police have reported to the prime minister.

Although Prime Minister Pashinyan approved the plan to re-establish the ministry in February 2021, the process did not conclude until the spring of 2023.

Patrol Police

In July 2021, the first Patrol Police Department was launched in Yerevan. This marked the beginning of a significant overhaul of the police, with the aim of creating a brand-new police force that would be seen as a “friend” to society.

The recruitment process for future Patrol Police officers was innovative and forward-thinking. Applicants had to pass a series of exams to be selected for a six-month course tailored specifically to their needs. The curriculum covered a wide range of subjects, including law, psychology, and philosophy, with the aim of equipping the Patrol Police officers with the necessary preparation for their service.

According to Ioannisyan, the number of crimes solved by the police in Lori and Shirak regions increased by 14 times in the first year of the operation (2022) of the Patrol Police. He further reveals that the police were reluctant to make this information public due to their dissatisfaction with the results of the Patrol Police Service.

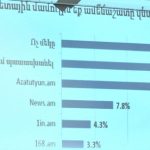

The successful launch of the Patrol Police Service led to an increase in public trust in the police. An IRI poll found that 68% of the country was “satisfied” with the police service, the highest figure since the 2018 revolution. However, the same poll found that trust in the police indicated a decline to 58% in 2023. Nevertheless, the police remained the second most trusted institution in 2023, following the Armenian Apostolic Church.

The effectiveness of the Patrol Police declined in 2023 compared to its early days. Ioannisyan cites the example of how the Patrol Police used to not hesitate to pull over high-ranking officials, but now apologize if they pull over a local government official. He argues that the system has worked hard to make the Patrol Police a “paper tiger” that is ineffective.

Failing the Reforms

The Pashinyan government’s reforms of the police and other institutions promised to bring long-awaited democratic changes to Armenia. However, while the country has made some progress in democratization, it has also faced setbacks and regressions, particularly after the country’s defeat in the 2020 Artsakh War.

Police reform has been no exception.

The turning point for Armenian civil society cooperating with the government for police reforms was the appointment of former Police Chief Vahe Ghazaryan as Minister of Interior.

As a result, the NGOs working on police reform abandoned the reform agenda and publicly refused to continue working with the government. One of the reasons for this backlash is Ghazaryan’s background and his alleged opposition to the reforms.

Ioannisyan claims that Ghazaryan bears personal responsibility for the failure of cooperation between the NGOs and the government, as well as the difficulties faced by police reforms. He has also alleged that the new police officers have become more brutal and violent since Ghazaryan’s appointment.

Ioannisyan accused Ghazaryan of promoting the return of a more brutal and violent police force, arguably worse than before the revolution.

New Level of Brutality

During last year’s Independence day ceremony’s Armenia’s Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan planned a visit to Yerevan’s military cemetery, with a number of relatives of fallen soldiers gathered at the cemetery to prevent Pashinyan from entering. As Pashinyan’s arrival time approached, the police forcefully moved in to remove the protesters, reportedly resorting to physical violence and even hitting civilians.

This incident raised concerns as one of the first publicly alarming cases of police brutality in post-revolutionary Armenia. However, many observers have pointed out that the “new” police force in the country has been consistently engaging in the same abusive practices as the old police force, as indicated by various indices and separate incidents.

According to a report by the Helsinki Civil Assembly Vanadzor, the number of reported cases of human rights violations by the local police increased by over 54% in 2022 compared to 2019 and by 20% compared to 2021, based on media reports.

In July, around 30 Armenian NGOs issued a statement condemning police brutality, which they claimed was becoming “systemic”. The NGOs slammed the government’s failure in reforming the police and judiciary, saying that the government “did not leave any room to claim the effectiveness of the reforms.”

The Police were seen using force against several parliament members, too, when trying to detain them during demonstrations. In a shocking precedent for at least the past decade, Armenian police used violence against lawyers who were fulfilling their duties. Three such cases took place in the first half of 2023.

“The first case that occurred in the Erebuni Police Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs may have given the impression that it was an isolated incident. However, after the second and third cases, it became clear that we are facing an alarming trend of police impunity,” the joint NGO statement stated.

In recent months, there have been several incidents where Armenian police officers have used violence. These incidents occurred in a Dilijan cafe, during the Yerevan Wine Days event, in the Poligraph club, and other places. However, law enforcement has not informed the public about the results of the investigations initiated.

The latest case of police violence in Yerevan was in September during anti-government protests amid Azerbaijan’s attack, the surrender of Nagorno-Karabakh and the mass exodus of the Artsakh’s Armenian population. The protesters, who gathered in front of government buildings for about a week, clashed with police several times; hundreds were detained and dozens, including police officers, were injured. Among those was senior opposition MP from the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF), Gegham Manukyan. The use of force by the police remains unaddressed by the government.

The increasing number of reports about police brutality and the worsening road safety situation raises questions about the effectiveness of the reforms planned and implemented in the last four years. Despite this, the Armenian government and government officials have not addressed these problems directly, occasionally condemning “any kind of violence”.